Over 50 years after the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the nations of the world are still determining which rights are human and which are national. This is especially clear in the case of the death penalty. The UN has adopted three separate resolutions on the death penalty, each calling for a moratorium with a view towards abolition. In 2010, the latest vote, the resolution passed 109 to 41 (with 35 abstentions). Human rights advocates and the UN’s own human rights commission agree that the death penalty violates the most basic human right, the right to life.

However, the right to life is still only guaranteed at the national level. The world was reminded of that this week when Texas executed a Mexican national, Edgar Tamayo. Tamayo was convicted of killing a police officer in 1994. He was an undocumented immigrant at the time of his arrest with a criminal history. However, his legal status in the US has no bearing on his status as a Mexican citizen and all foreign nationals have a right to communicate with their consulate for assistance when detained or arrested. In fact, under international law US authorities must inform foreign nationals of that right “without delay”.

Edgar Tamayo’s national citizenship may have been able to save his life. He was not informed of his consular rights until after the trial had already begun. Mexico, having abolished the death penalty in 2005 and execution free since 1937, seeks to prevent the execution of its citizens abroad. While no comprehensive study has been completed, preliminary evidence suggests that consular assistance reduces the chance that the death penalty will be sought or imposed.

Despite, or perhaps because of the potential for diplomatic intervention, one study found that out of more than 160 foreign nationals given a death sentence in the US only 7 had been informed of their consular rights in a timely manner. The vast majority only learned about this right weeks, months, or even years after their arrest and often from someone other than local authorities. Currently 141 immigrants are on death row, 59 are Mexican–the next most populous nationality is Cuban at 10. It is worth noting that only five of these immigrants were undocumented at the time of arrest.

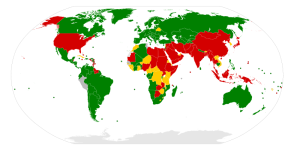

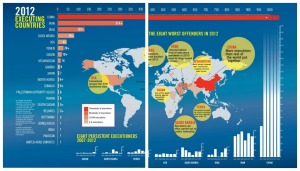

Only 21 countries executed people in 2012, while 58 countries imposed the death sentence. While the global trend has been away from the death penalty, there is little an abolitionist state can do to prevent their citizens from being executed in retentionist states. They can refuse to extradite (regardless of nationality) unless assurances are given that the death penalty will not be sought. And, they can provide counsel and resources for their own citizens should they find themselves facing the death penalty abroad. The UK, for example, does not shy away from using political influence to prevent the execution of their citizens, stating clearly on a government site:

The UK opposes the use of the death penalty in all circumstances and will use all appropriate influence to prevent the execution of any British national. We intervene at whatever stage and level is judged appropriate from the moment a death sentence becomes a possibility. We will lobby at a senior political level when necessary, and did so in 2012 in a number of countries.

Since 2000, the United States has executed 15 foreign nationals, with 2 more scheduled for execution in 2014. It is clear that consular intervention can make all the difference. Nationals of states that believe the death penalty violates human rights can lean on the rights guaranteed by their nationality, in this case the right to life but this is no guarantee. The US State Department and Mexican authorities called for a halt of Tamayo’s execution but in death Tamayo, unfortunately, had only the human rights of a US citizen.